Foraging in the garden (and beyond) for edible flowers and leaves, Foraging and gardening resources, Recipes: Wild garlic pesto, Dandelion cordial, Nettle bread.

Cardoon stem, Feverfew, Rhubarb flower, Marjoram, Apple blossom, Chives, Hawthorn leaves and flowers, Beech leaves, Salad burnet, Purple sprouting broccoli flowers, Thyme leaves and flowers, Landcress flowers, Bay leaf and flowers, Forget-me-not, Rose, Rosemary leaf and flowers, Mint leaves, Marigold, Sorrel, Dead Nettle, Dandelion, Oxalis leaf, Hops growing tip and leaf, Vine leaf, Fennel leaf, Clover leaf and Sage flower.

.

“Have nothing in your garden that you do not know to be useful and believe to be beautiful”

Mis-quoted of Willam Morris

.

My 7-year-old son and I were in the garden, doing “school”. I explained to him that when we had planned the back garden 7 years ago, it was to be almost entirely edible and that I had aspired for the garden to be beautiful, with as many edible leaves and flowers as possible. Over the years many plants have self-seeded, and they have been allowed to stay if they are good pollinators; so the space is always evolving. We set ourselves the challenge to identify as many seasonal edible leaves and flowers as possible (from plants not eaten very widely).

Many of them are arranged on the board above, some of them are described below.

.

A salad, foraged from plants in our garden

Marigold, Calendula officinalis

A subtle peppery flavour.

“Throw a handful of petals across just about any dish for instant sunshine. At home with sweet and savoury dishes, they have tradionally been used for their colour above all else. Ground up – a good alternative to saffron, turning sauces or butter golden. Their oil can be made into a golden salad dressing. Scatter petals over salads and fruit, or floating in a drink”.

Advice from Lia Leendertz in her book: Petal, Leaf, Seed.

Forget-me-not, Myosotis scorpioides

Nothing particular about their flavour; descibed as “fresh”.

A perfectly designer flower that looks beautiful floating in a drink, or candied on a cake.

Beech leaves, Fagus sylvatica

This was an delightful discovery. I had read about them in Martin Crawford’s book Creating a Forest Garden. Working with nature to grow edible crops.

He describes the young leaves as having a lemony flavour, which my son and I would agree with. We both liked the flavour and the texture. Crawford recommends picking the leaves within 3 weeks of leafing for the best flavour, so you may have to wait until next year.

New Zealand Tree Spinach (Chenopodium giganteum ‘Magenta Spreen’)

Alys Fowler writes about NZ tree spinach: “The flowering sprouts have a blue-green leaf and a dusky purple midrib and veins. The tree spinach is a brilliant bright green with each new set of leaves blushed a shocking magenta. Eventually the tree spinach will reach 1m or more … The tree spinach, as its name suggests, is a spinach substitute. It is fantastic melted in butter and keeps its magenta when cooked. It can also be eaten very young raw in salads. Once it’s tall, it does become a lot coarser.

You can sow it either as seed (which there is still time to do now) or buy a young plant and let it do the job for you. One word of warning: it will reappear everywhere. It is not exactly a thug, but if you’re not prepared to eat it, that’s an awful lot of weeding. If you sow it as seed, consider sowing it in modules or seed trays and planting it out as this will give you more control as to where to grow it. If you want full-height plants, it needs to go at the back of the border. I planted mine this way and harvested very little, allowing it to set seed, and then I uprooted the plant and shook it wherever I thought it might look nice next year. You can pinch out the growing tip for a bushier plant.”

I bought one plant maybe 5 years ago, and every year it appears again. I think it is very pretty but we have only eaten it when it was small.

Hop, Humulus lupulus

Hops are best know for the role of their cone-like fruit (which appear in September) in brewing beer, first started in Holland and Germany and then incorporated into British brewing practices. Their role in the kitchen also has a connection with the brewing business in the past. During the pruning of the cultivated hop vines in May (often done by gangs of volunteer labour), the pruned shoots (top 10cm) were tied in bundles and cooked as asparagus. The practice was mentioned by Pliny, the Roman author and naturalist. They are often eaten in Italy, along with many other green stem wild vegetables, with egg – as a frittata.

As described by Richard Mabey in his book Food for Free.

Hop leaves, small fresh ones, can be eaten as spinach or in a salad – more of a slight bitterness and hoppy flavour. I’m looking forward to eating the hop flowers, apparently quite a delicacy.

Dead nettle, Lamium purpureum

Dead nettle, although superficially similar to true nettles in appearance, is not related and does not sting (hence the name “dead-nettle”). Purple dead-nettle is actually in the mint family. It is highly favoured by the bumble bee and and makes a very early appearance as a nectar plant. They are found almost anywhere; gardens, meadows, woodlands.

The whole purple dead-nettle is edible. It has a mild, slightly grassy/ somewhat floral flavor, and the purple tops are even a little sweet. The small ones are considered by some a real delicacy. I very much liked it, I had not known they were edible until now and have removed many from vegetable beds over the years. They can be eaten in many ways: salads, pesto, soups, tempura batter or stir-fry.

It is likely that this plant was introduced to Britain with early agriculture and evidence for it has been found in Bronze Age deposits.

Stinging Nettle, Urtica dioica

“Nettles: Barbed and bristled and undeniably stingy as they are, these plants are nevertheless a gift to anyone who favours cooking with local, seasonal, fresh ingredients. They thrust themselves up from the barely warm ground as early as February (nettle soup on Valentine’s Day is a tradition in our house), then grow with untrammelled enthusiasm right through the spring and summer … the fresh, young growth of March and April is the crop to go for. Pick only the tips – the first four or six leaves on each spear – and you will get the very best of the plant. Keep your eye out throughout the late summer and autumn, though, because young crops of freshly seeded nettles will grow wherever they get a chance…the strimmer is the nettle gourmet’s friend: nettles that have been mown down will reliably put up a burst of fresh growth.

Not only does this plant taste good, but you can almost feel it doing you good as you eat it. Particularly rich in vitamin C and iron, a tea made by steeping nettle leaves has long been a tonic. But I prefer to eat the leaves themselves. The flavour is irrefutably “green”, somewhere between spinach, cabbage and broccoli, with a unique hint of nettliness: a sort of slight, earthy tingle in the mouth. If you like your greens, you’ll like nettles”. Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, (article link is in green) includes a number of nettle recipes.

I descibe how to blanch them, to remove the sting, in the recipe section below. I was so excited to discover how easy it was to cook them and wondered how and why I never had done before!

Landcress or Wintercress flower buds, Barbarea verna

This flower is so vibrant, they look amazing in a salad. They taste like a little bite of watercress, and texturally they have a juicy bite.

Land cress is often cultivated as a salad plant, when it is usually treated as an annual. It can supply leaves all year round from successional sowings. In hot weather plants soon run to seed unless they are kept shaded and moist, but that is when the flower buds form.

Wild Food Girl reports “I find all I have to do is drop the wintercress into boiling water in an open pot for one or two minutes, rinse with cold water to stop the cooking, and then it’s ready for whatever preparation I want … I like to use the leaves or the unopened bud clusters and top 2 inches or so of soft stem. It’s slightly more bitter if the clusters have started to spread apart, but it’s nothing a dash of lemon juice can’t fix. They are also thick and juicy. Truth be told, I really have come to crave wintercress.”

Blackcurrant leaf

“Blackcurrant leaves are an excellent place to start for inspiration (when eating garden leaves). Standing in a blackcurrant fruit cage in a fog of heady berry-scent, you can quite easily assume that it comes from the berries themselves. Crumple a leaf in your hand though, and smell the delicious jammy-blackcurrant notes. When steeped in any warm liquid, they obligingly release their flavour, making the leaves an unexpected – but wonderful – flavouring agent for cordials, sorbets and jellies, as well as this delicious Blackcurrant leaf ice cream recipe.” Rachel Walker, in The Food I Eat blog; Cooking with Leaves.

These were such an exciting find. The scent and taste of the leaf is so like an intensely concentrated blackcurrant syrup – far more than eating a berry itself. They are so delicous eaten from the bush, although we only have one bush so have had to limit myself. They haven’t made it to a salad yet.

Dandelion, Taraxacum officinalis

Derek Markham descibes: “The quintessential garden and lawn weed, dandelions have a bad reputation among those who want grass that looks as uniform as a golf course, but every part of this common edible weed is tasty both raw and cooked, from the roots to the blossoms. Dandelion leaves can be harvested at any point in the growing season, and while the youngest leaves are considered to be less bitter and more palatable raw, the bigger leaves can be eaten as well, especially as an addition to a green salad. If raw dandelion leaves don’t appeal to you, they can also be steamed or added to a stir-fry or soup, which can make them taste less bitter. The flowers are sweet and crunchy, and can be eaten raw, or breaded and fried, or even used to make dandelion syrup or wine. The root of the dandelion can be dried and roasted and used as a coffee substitute, or added to any recipe that calls for root vegetables.”

According to Jennifer McLagan in her cookery book Bitter, eat dandelions raw with a hot fatty dressing to mitigate their bitterness and soften their sturdy leaves. Braising also softens them and mellows their bitterness. Easy to prepare, just rinse well and trim the thick stems. They are rich in vitamins A and C and iron.

The name comes from the French expression dents de lion or ‘lions teeth’, in reference to the shape of the plant’s leaf.

Creeping wood sorrel or Oxalis, Oxalis corniculata

Oxalis corniculata has a creeping habit and small yellow flowers followed by upright seed capsules. A purple-leaved colour variant is quite common. Leaves are edible, raw or cooked. They can be added to salads, cooked as a vegetable with other milder flavoured greens or used to give a sour flavour to other foods. Flowers can also be eaten. They have a pleasantly sour lemony taste. The leaves contain between 7 – 12% oxalate so use sparingly, but it’s unlikely you’d pick more than a few as the leaves are very small and fiddly to harvest.

Interestingly (perhaps!) according to one source a slimy substance collects in the mouth when the leaves are chewed, this is used by magicians to protect the mouth when they eat glass. The boiled whole plant yields a yellow dye.

Sorrel, Rumex sanguineus

There are a few varieties of sorrel, mine is a red veined and also known as the “bloody dock”. The type of sorrel most often used in french cookery is greener, but I think mine is a pretty ground cover. The leaves have a lemony taste – due to the oxalic acid, so some caution is adviced and it has been suggested that you don’t eat sorrel soup (or rhubarb and other oxalic acid containing plants) every day of the week!!

“This bright green leaf is startlingly, puckeringly sour and lemony, but with a wonderful lightness: it tastes green, it tastes of spring … It is quite possibly the easiest crop in the world to raise (though really not that easy to buy). It’s one of my favourite leaves to eat and cook with in spring and early summer. Sorrel’s spear-shaped leaves are among the first to unfurl themselves from the warming ground in February or March, and provide the perfect antidote to the hearty, earthy flavours of winter. It can function as a herb, a salad leaf or a vegetable, giving you either a thread of lemony flavour or a real, mouth-filling whack of it, depending on how much you use … In larger quantities, sorrel’s acidity requires a little tempering … it adds such a lovely edge to creamy and delicately flavoured foods – everything from creme fraiche or oil to potatoes, pulses, eggs or chicken.” Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, in the Guardian

May Flower or Hawthorn, Crataegus monogyna

According to Rosamond Richardson in her book Hedgerow Cookery (which I bought at Marple Library for 50p in a sale of their books when I was a teenager. I have also recently discovered she was a family friend of a friend of ours, and he recalls her great enthusiam): “In folklaw the budding of the may tree signifies the end of winter and heralds the coming of spring: hence the origin of May Day (which used to fall on what is now May 12th – when the flowering is at its peak – until 1752 when the Julian calendar changed to the Gregorian calendar and 11 days were ‘lost’). Tradionally, young girls bathed in the hawthorn dew on May Morning in the hope of becoming more beautiful, as recorded in the nursery rhyme:

The fair maid who the first of May Goes to the field at the break of day, And washes in dew from the Hawthorn tree, Will ever after handsome be.

Above all the Hawthorn is a symbol of rebirth and life. Which is a lovely thought, as the prolific hawthorn blossom for a few miles of the roadside is deeply etched in my memory, as I came home from the hospital with my first-born child on the 12th May.

Hawthorn is the most commonly planted hedge shrub in Britain: ‘haw’ is from an old English word for hedge.

Very young hawthorn leaves have always been eaten and are traditionally known as ‘bread and cheese’ (possibly because they were eaten with bread). They work well in a salad (apparently good with potato and beetroot) and have taste mildly nutty. The blossom has a pleasant flavour, if picked in sunshine and full bloom. They can be made into wine or a liqueur.

Flowers of Herbs

Many of the flowers of herbs are delicious in their own right. Many of the tiny flowers or florets are a slightly milder form of their leaves and something more; a beautiful little parcel of flavour. At this time of year, I very much like thyme flowers in a drink and chive florets are stunning in a salad.

Sally Next writes: “I used to be a bit sceptical about all this new-fangled fashion for eating flowers. Well. Then I ate a rosemary flower. And found out about the flavour, and why people who eat flowers tend to eat rather a lot of them. I’m left with the feeling that for the last 20 years or so of my veg-growing life I’ve missed out on the best bit of my crop.”

Other flowers in the garden that you can eat in the spring

Rose petals are well-known in Middle Eastern cuisine, but the rose was used for centuries in English cooking until it felt out of favour. There are many roses that grow well in Britain that are highly scented and suitable to use in cooking and baking, or flavouring alcohol or distilling to make rosewater. I had never eaten apple blossom until this project – and loved it (not too much because of cyanide, which is also in the pips – but you’d have to eat an awful lot and they are high in antioxidants and minerals). Lilac is considered a love it/hate it flavour. I adore the scent of lilac and to me it was as tasty as it smelt in a couple of the blossoms that I snaffled from my local streets on my “COVID-19 daily walk” and foul from another couple – you’d need to know your bush! A friend suggested that she might make a flavoured vodka – which sounds a great idea. As does a Peony vodka, which I was sure that I’d read about in Mark Diacono’s blog (he tries all kinds of things and I really enjoy his Otter Farm Facebook posts. You can search for his vodka infusions in the search bar). But I did find this recipe for a Peony syrup – but I haven’t tried it myself. My four plants haven’t flowered yet this year, so they don’t make the hall of fame in this blog, but as I am home ‘so much’ at the moment, I am going to make the syrup when they do. You can find out more about edible flowers in the Edible Flower Guide from the seed company Thompson and Morgan or from one of the books listed in the resources section. Lia Leendertz’s book Petal, Leaf, Seed. Cooking with treasures of the garden is packed full of ideas, as incidentally are her almanacs.

A foraged garden salad

And so we feasted on the fruits of our labours… our combined favourites were: beech leaf, blackcurrant leaf, apple blossom, landcress flower, hop growing tip and dead nettle. Almost everything!!

Plants for a future (PFAF) a database of edible plants

If you try this yourself please don’t rely on my information; use a reputable idenfication guide and perhaps double check edibility on the PFAF database (see resources page for further information about PFAF and their suggestions of top edible plants).

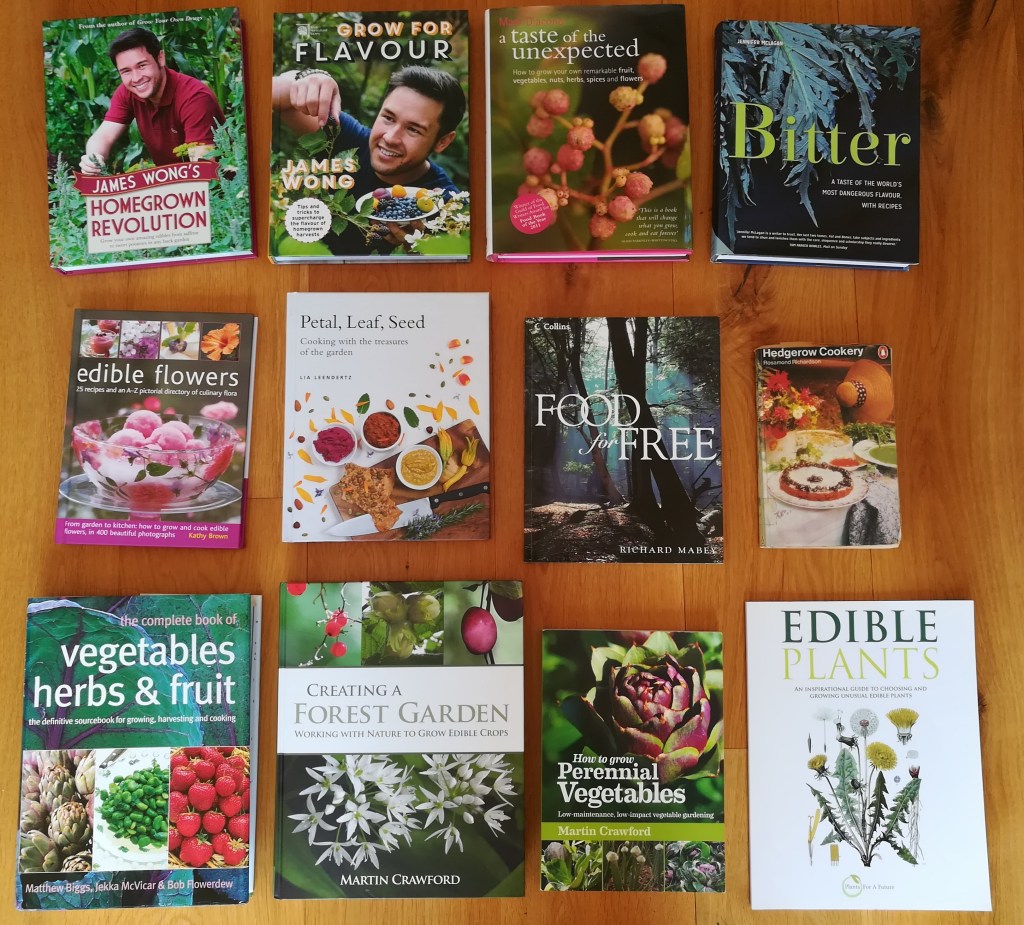

Books: foraging and unusual gardening

These are some of my favourite books, and others including The Forager’s Calendar by John Wright, as well as a number of blogs and websites – will be listed soon in the Download section.

Foraging beyond our garden

A few days ago, during “lockdown”, I was fortunate to be told about a free online zoom session being run by Woodland Classroom. It was a fabulous inspiring hour. The couple shared information about: identification, location, photographs, food uses, tinctures, teas, alcoholic drinks and claimed medicinal benefits. I look forward to attending one of their courses near Wrexham in North Wales (when the limitations due to COVID 19 are lifted). There are so many plants that are easy to find and sound very tempting to eat. They highlighted that the taste for ‘wild food’ can sometimes take a little while to aquire; so many of us are used to the taste of the supermarket breed for cultivation vegetables, which are often relatively bland and flavour may be lost in cold-storage. I have owned a number of foraging books for a while, but I have never been very confident going out to pick from the countryside – aside from elderflowers, blackberries and sloes. My son and I went for a short walk to our local nature reserve and came home with: nettles (to make a second loaf), garlic mustard, hawthorn leaves and flowers and an elderflower.

Picking wild flowers and the law

Advice from the organisation Plant Life, which is a British conservation charity working nationally and internationally to save threatened wild flowers, plants and fungi .

“Contrary to widespread belief, it is not illegal to pick most wildflowers for personal, non-commercial use. In a similar vein, it’s not illegal to forage most leaves and berries for food in the countryside for non-commercial use. Legislation under the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981) makes it illegal “to uproot any wild plant without permission from the landowner or occupier” in Britain. The term ‘uproot’ is defined as “to dig up or otherwise remove the plant from the land on which it is growing”. Picking parts of a plant (leaves, flower stems, fruit and seed) is therefore OK, as long as you don’t remove or uproot the whole plant.

However, you should not pick any plant on a site designated for its conservation interest, such as National Nature Reserves (NNRs) and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI’s) in Britain and Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI’s) in Northern Ireland. Permission for picking from these sites requires prior consent from the appropriate statutory conservation agencies (English Nature, Natural Resources Wales, Scottish Natural Heritage or the Environment and Heritage Service, Northern Ireland). It is illegal to pick, uproot or remove plants if by-laws are in operation which forbid these activities, for example on Nature Reserves, Ministry of Defence property or National Trust land.

In addition, both the Wildlife and Countryside Act and the Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order include a list of highly threatened plants that are especially vulnerable to picking, including plants like Deptford pink, alpine sow-thisle, wild gladiolus and several orchids and ferns (as well as fungi, lichens and bryophytes). No part of these Schedule 8 species can be intentionally picked or uprooted without a licence from the appropriate statutory conservation agency. These plants are also protected against sale.

Finally, picking of wildflowers is also specifically covered under the 1968 Theft Act (England and Wales): “A person who picks mushrooms growing wild on any land, or who picks flowers, fruit or foliage from a plant growing wild on any land, does not (although not in possession of the land) steal what he picks, unless he does it for reward, or for sale or other commercial purpose”. However, the same restrictions apply to picking on land designated for its conservation interest as described above.”

Snowbell or Three-cornered leek, Allium triqetrum

I spotted a clump of these by the side of my friend Jane’s driveway. I recognised it as I had taken the first photograph on the SW coastal footpath in Cornwall one May, as I thought it so beautiful – but also suspected it was edible as it smelt like wild garlic! I haven’t yet tried one, but I intend to plant some in my garden for next year.

“All of the plant is edible. The young plants can be uprooted when found in profusion and treated as baby leeks or spring onion, the leaves and flowers can be used in salads or the leaves in soups or stews, the more mature onion like roots can be used as onion or garlic …The flower stem is like the leaves but more triangular in profile than the leaves, hence the common name, Three-Cornered Leek. ” from wildfooduk.com

Jack-by-the-hedge, Hedge garlic, Garlic mustard, Alliaria petiolata

Jack-by-the-hedge smells mildly of garlic and tastes of mustard. Culpepper recommends the use of young leaves in salads. The leaves can be finely chopped and added to a butter, or put in a cheese sandwich. They would make a good pesto.

Cowslip, Primula veris

Cowslips are synonymous with spring and Easter. The botanical name means “the first little one in spring”. At one time cowslips were found in vast numbers along verges and in meadows, but they have declined in the wild, so it is best to grow them yourself. I have one plant in my garden, and it is still flowering today after many weeks.

The flowers and leaves are edible and rich in Vitamin C. The leaves are often used in Spanish cooking; they have a slightly citrusy flavour. Here in the UK the plant has traditionally been used to make jam, wine, tea and ointment. Cowslip wine was said to steady the nerves due to its analgesic properties. The plant contains an oil known as ‘primula camphor”, containing many flavonoids (phytonutrients, often found to have health benefits). Nowadays the flower is more often used as a salad decoration or floating in a drink.

William Shakespeare refers to the cowslip on a number of occasions in his plays, one of them being “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” when Puck first meets the fairy (Act 2 Scene 1), the fairy replies:

Over hill, over dale

Thorough bush, thorough briar

Over park, over pale

Thorough flood, thorough fire

I do wander everywhere

Swifter than the moon’s sphere

And I serve the Fairy Queen

To dew her orbs upon the green.

The cowslip tall her pensioners be

In their gold coats, spots you see,

Those be rubies, fairy’s favours

In those freckles live their saviours

I must go seek dewdrops here

And hang a pearl in every cowslip’s ear.

Old British myths claimed that fairies sought refuge inside cowslips in times of danger. Cowslips were dedicated to the goddess Frigga/Freya in Norse mythology and they played a part in the remedies of Celtic druids. The flowers resemble a bunch of keys and are sometimes called Herb Peter – St Peter’s emblem is the keys of heaven.

Recipes

Guest recipe of Wild Garlic Pesto with photograph from Anthea Wratten. Thank you. It sounds delicious, and I suspect there are many wild greens that could be substituted for the wild garlic (perhaps the triquetal leeks), as their season is almost over.

“This is delicious thrown through pasta, swirled through soups and stews or served as a condiment to baked potatoes or a perfectly roast chicken. Try using it as a salad dressing or popping a few dabs into your favourite sandwich. Will keep for at least a week in the fridge. Feel free to replace the hazelnuts with any nut of your choosing, likewise any salty hard cheese can work too. Makes 1 large jar.” Riverford Recipes

Dandelion cordial

- Dandelion flower heads (100g)

- Water (350ml)

- Sugar (300g)

- Slice of lemon

- Piece of vanilla pod (optional)

- Select a big bunch of dandelion, all bright and open (as the light-level drops, the flowers close up).

- Rinse in water, and leave for a couple of minutes to allow any little insects to leave!

- Remove the petals and place in a saucepan with the water, trying to avoid adding the green part of the flower as it will change the colour of the drink.

- Simmer with the lid on for 15 minutes.

- Switch off the heat and leave to infuse overnight.

- Strain using a sieve (or muslin) and weigh the fluid.

- Add as much sugar as there is dandelion infusion.

- Heat gently to disolve the sugar and then boil for 10-15 minutes until you reach your prefered consistancy of syrup.

- Pour into a sterilised jar and keep in the fridge.

Blanching Nettles

We cut the tips and the top 4-6 leaves of all the nettle plants I could find in our garden, washed them briefly and then dropped them into boiling water for 30 seconds. We removed with tongs, and dropped into very cold water, to prevent them cooking further and so retain their vivid green colour.

This quick heat denatures the sting. Incidentally you can still use the blanching water for cooking, the nettle water is not contaminated. After blanching, you grit your teeth and pick them up to chop them, discovering it is OK and now feels as if you are handling any herb.

Nettle Bread

I mixed a large bunch of chopped blanched nettle tops into the risen bread dough that I had prepared and left to prove. Baked as usual. I can’t wait to forage some more.

Comments and Guest posts

I would be delighted if anyone would like to comment, or start a conversation about anything they have read. Or if anyone would like to send me a recipes, photographs or any other information that I could include in a future post.

First of all, your title of your blog is very good. And this entry is full of beautiful photographs and amazing ideas. I like the New Zealand spinach one best. Maybe you could save me some seeds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To add to your information on responsible foraging there is a 1 in 20 rule… see the BSBI code of conduct. Do not pick unless there are at least 20, then only pick one of them.

https://bsbi.org/download/8415/

Keep it up!

LikeLiked by 1 person