Brussels Sprouts

BRUSSELS SPROUTS

Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera

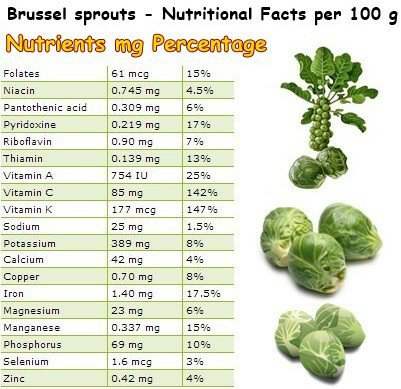

Brussels Sprouts are one of the cruciferous vegetables, part of the brassica family of vegetables (the largest vegetable family known – including cabbages, cauliflowers, broccoli, collards/ spring greens, kale, kohlrabi, turnips, and swede). Cruciferous (“cross-bearing”) from the shape of their flowers, whose four petals resemble a cross. They are unique in that they are a rich source of sulfur-containing compounds called glucosinolates (β-thioglucoside N-hydroxysulfates) that impart a pungent aroma and bitter taste and considerable health benefits. All cruciferous vegetables are packed full of antioxidants and other phytochemicals. Brussels sprouts are one of the stars – now known to top the list of commonly eaten cruciferous vegetables for glucosinolate content.

The Brussels sprout is grown for its edible buds which are typically 1.5–4.0 cm in diameter. They’re at their best from November – January. They are thought to have originated in Rome, where they were developed from a form of kale-like wild cabbage. However they was brought to Europe in the 5th Century and had become very popular by the 16th century in Belgium, after it was cultivated in the 1200’s near its namesake city of Brussels.

But their popularity in Europe today is highest in the UK. Even though British farmers produce nowhere near the number of sprouts they do in Holland, the “Great British Public” actually consume the most Brussels sprouts in the whole of Europe. It is definitely a festive choice, however, as an impressive two thirds of the overall number of sprouts eaten in the UK are consumed during the Christmas period!

And apparently there is actually a possible genetic reason why you and your family may love sprouts whilst your partner and in-laws hate the little green gaseous bombs? Apparently, according to this article, there’s a gene which controls whether we taste the chemical PTC – a chemical very similar to chemicals found in sprouts… The Brussels Sprouts Gene – TAS2R38

Until a few years ago, I absolutely loathed Brussels sprouts. They made my stomach churn at the thought of them – disgusting. Then one day I was eating lunch in a little cafe in North Yorkshire when I asked what was in the completely delicious orange and nutty coleslaw I had just devoured. WHAT!! WHAT!!!! I was told that I had just eaten raw Brussels sprouts – and I had to acknowledge the fact that I had really enjoyed them!

As a consequence I have given the Brussels sprout a second chance and have discovered that there are many wonderful ways to prepare them. I agree with the writer who says: “Brussel sprouts suffer from a truly undeserved poor reputation” … he says ” When prepared properly by gently steaming, Brussels sprouts have a sweet, nutty flavor and a crisp texture. If overcooked, Brussels sprouts produce a strong foul odor and become mushy in texture. An overcooked Brussels sprout is truly vile, while a steamed Brussels sprout topped with garlic butter or Hollandaise sauce is a gourmet delight”. Personally I prefer them in a coleslaw, or roasted – perhaps with chestnuts or they’re amazing flash fried with garlic alongside a piece of smoked Mackrell. As a legacy of former experiences, I’m not sure I am ready to try them steamed in a Hollandaise sauce. Perhaps I’ll overcome that historical and of so, will report back here one day …

I have attempted to grow Brussels sprouts this year in the garden, although I’ve not had a great crop. I suspect they needed more compost and were outcompeted by the strawberries which are over-running our garden. But here’s the photo before I picked them for today’s recipe (supplemented by my Riverford veg box supplies in the fridge).

The sprout tops are usually cut off (now I know) to encourage the growth of the sprouts on the stalk – much like pinching out tomatoes. Riverford says of them: “Once seen only as a grower’s perk, they are pleasantly bitter, like good kale, but less dense than a winter cabbage”.

Goes well with

Acidic flavours (Lemon, Vinegar)

Anchovies

Cured pork

Dairy

Cheese (hard or blue)

Herbs

Nuts

Mustard

Onion

Spices (Pepper, Carraway, Chilli, Nutmeg, Mustard seeds)

So, on the Eleventh Day of Christmas, I bring you for brunch:

BRUSSELS SPROUTS, EGGS AND BACON with Cacik.

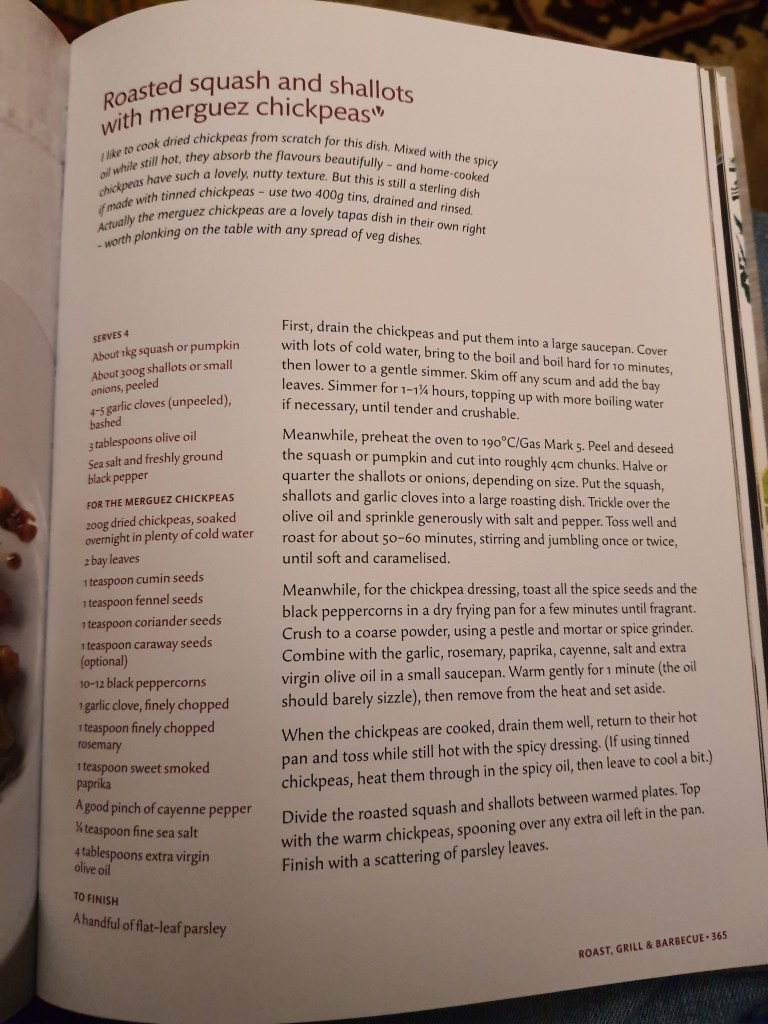

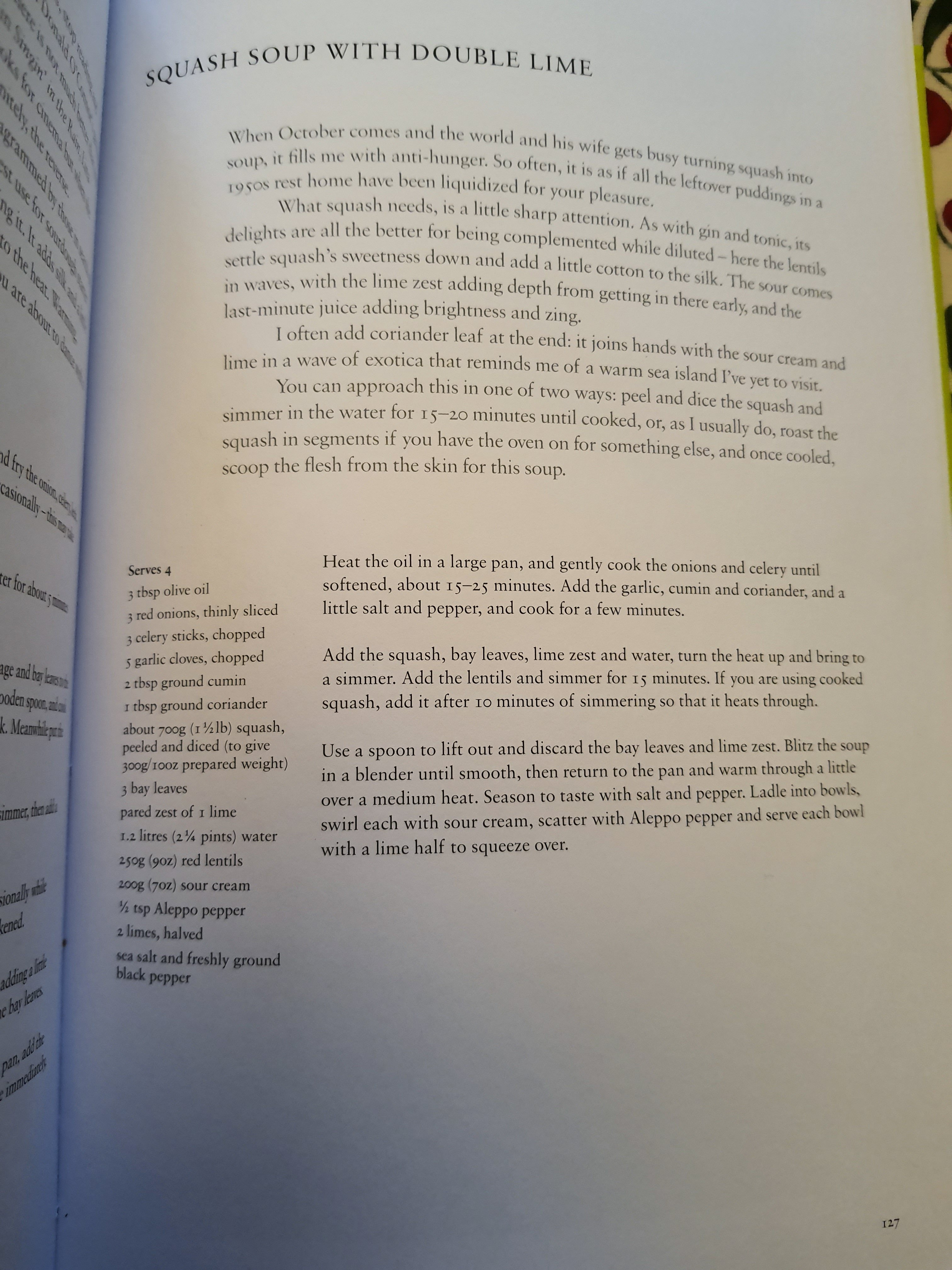

Recipe – with my modifications

INGREDIENTS:

- 1 Tbsp balsamic vinegar

- 1/2 tablespoon olive oil – good glug

- 1 cloves garlic, diced

- 400g brussels sprouts, halved/ quarted large (I only had 200g due to wastage – keeping then too long in the fridge. So I supplemented with mushrooms and sliced ramiro peppers (totalling 200g)

- 4 slices streaky bacon, diced

- 4 eggs

- 2 tsp pul biber (Aleppo pepper)

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper

- 1 Tbsp chopped fresh dill

DIRECTIONS:

- Preheat oven to 220 °C

- In a small bowl, whisk together balsamic vinegar, olive oil, garlic; salt and pepper, to taste. Add Brussel sprouts, any supplementary vegetables, the bacon and coat well .

- Place Brussels sprouts and bacon mixture on a single layer on a baking sheet (with a lip)

- Place into oven and bake for 20 minutes, or until tender. Turning regularly.

- Remove from oven and create 4 wells, gently cracking the eggs into them – keeping the yolk intact.

- Sprinkle eggs pul biber; season further, to taste.

- Place into oven and bake until the egg whites have set, an additional 8-10 minutes.

- Serve immediately, garnished with herbs if desired, (I used dill).

Cacik with dill

Ingredients (serves 2)

- 1/2 cucumber, quartered lengthways and coarsely chopped or grated

- 1/2 garlic clove minced

- 250g tub Greek yogurt

- 1/2 x 25g pack dill, fronds chopped

- 1-2 tbsp extra-virgin olive oil, plus extra to serve

- sea salt (flakes give some crunch)

- a pinch of pul biber (my new favourite spice – mind heat, sweet yet savoury)

Mix minced garlic with yoghurt and olive oil. Stir in must of dill dill and all the cucumber. Drizzle with a little more oil, pinch of pul biber, the salt and the reserved dill.

It was sweet and bitter, salty and lightly spiced.

Other sources of information:

- https://www.riverford.co.uk/a-to-z-of-veg/brussels-sprouts

- https://www.foodrepublic.com/2013/02/19/11-things-you-probably-did-not-know-about-brussels-sprouts/

Tally for the month

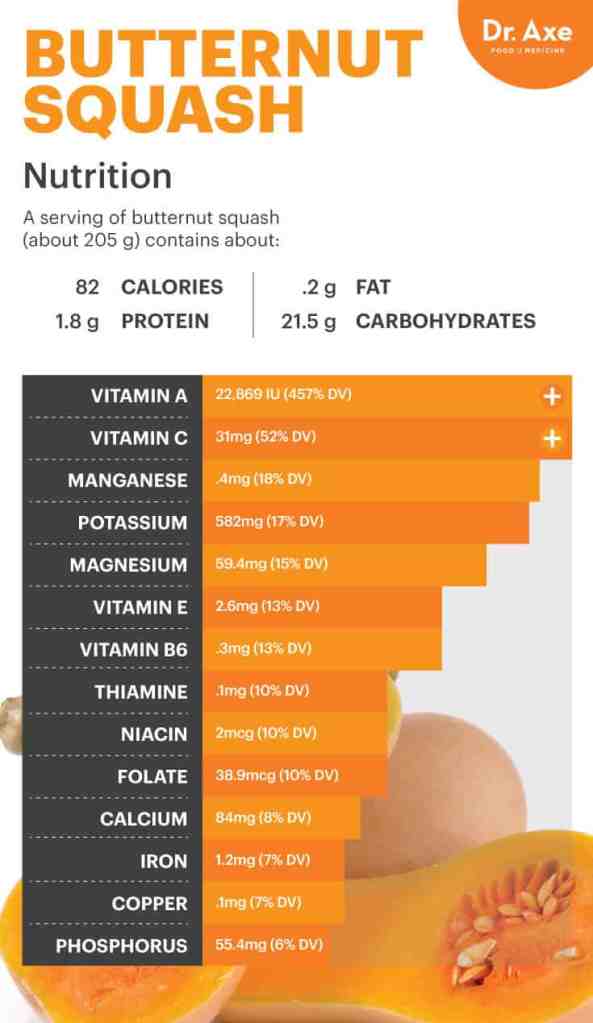

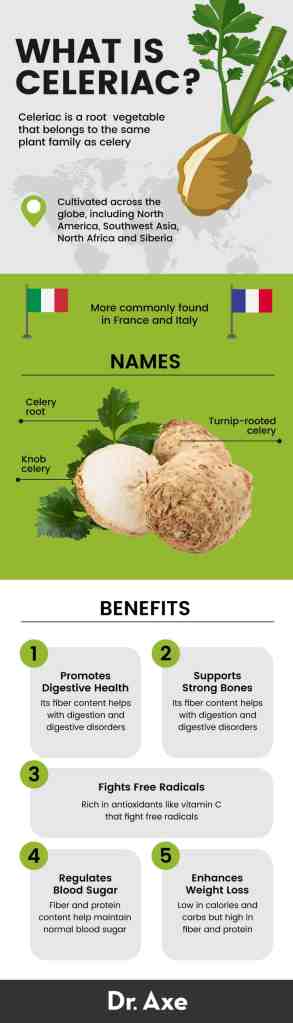

Main Vegetables: broccoli (calabrese), Brussels sprouts, butternut squash, celeriac, radicchio

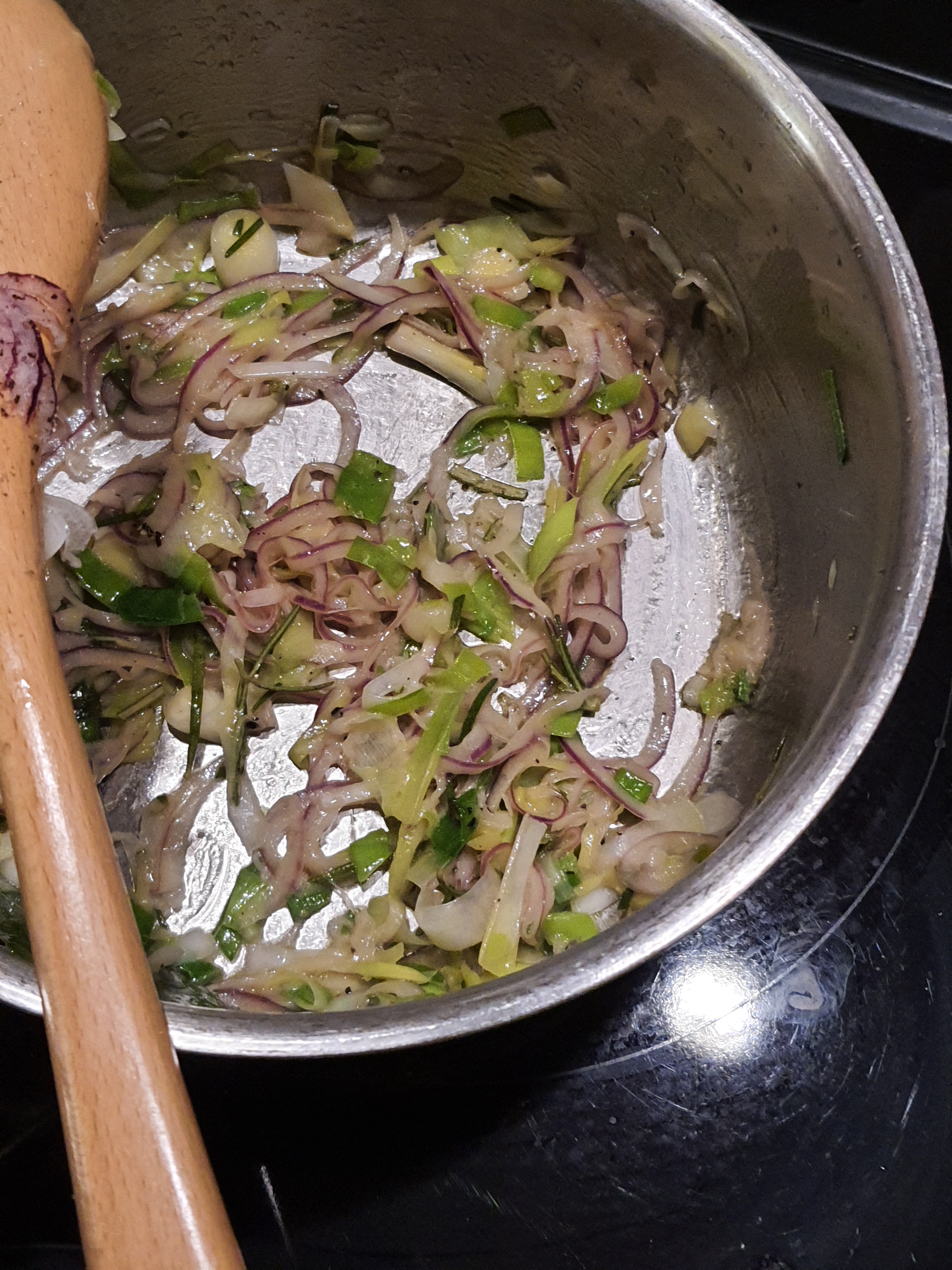

Subsidiary Vegetables: onion, shallots, garlic, leek, celery, potato, rosemary, carlin peas, chick peas, kale, chilli, dill, cucumber, mushroom, ramiro pepper.

Subsidiary Fruit and Nuts: lemon, fig, walnuts